By Susan McVie

Over the last twenty years, Scotland’s success in reducing violence has been attributed to many factors, but one thing is abundantly clear: it’s children and young people who have paved the way for change.

Trying to measure behavioural change amongst young people is not easy, as large-scale surveys typically focus on adults, and police recorded statistics rarely tell us about the behaviour of individual people. However, two large Scottish cohort studies conducted twenty years apart show a remarkable drop in offending behaviour – including violence - amongst those in early adolescence.

The Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime (ESYTC) involves a cohort of 4,300 young people born in 1986/87. First surveyed at the start of secondary school (age 12), the ESYTC asked young people about their involvement in various types of offending. Now in their mid-30s, the study continues to examine patterns of offending across the life-course and has a wealth of data to identify how childhood factors influence experiences in adulthood (McAra and McVie 2022).

The Growing Up in Scotland (GUS) study started following a cohort of around 5,200 children at birth in 2004/05. When they reached age 12, GUS included questions on nine types of offending behaviour – taken from the ESYTC – so that the prevalence and nature of offending amongst these two cohorts of young people could be compared. The most recent findings from the GUS cohort at age 14 have just been published (Scottish Government 2022), allowing us to examine how youth offending has changed over a twenty year period

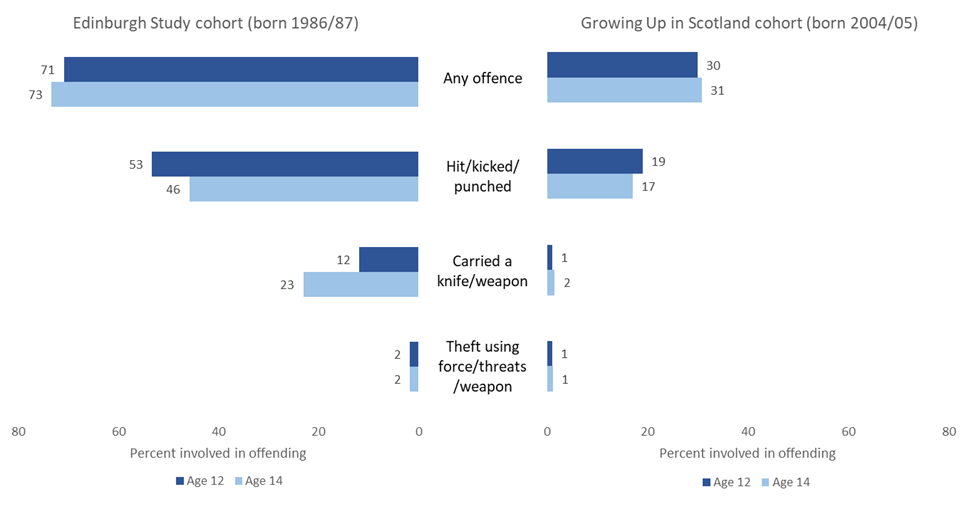

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of self-reported offending at age 12 and age 14 for both the ESYTC and GUS cohorts, and demonstrates just how adolescent behaviour has changed over time. Around seventy percent of ESYTC cohort members reported involvement in at least one type of offending in early adolescence; whereas, amongst the GUS cohort this has reduced to around thirty percent.

Looking more specifically at violent offending, the prevalence of physical violence (including hitting, kicking and punching others) has declined from around half of the ESYTC cohort to less than a fifth of the GUS cohort. Involvement in violent forms of theft (using force, threats or a weapon) have remained reassuringly low for people of this age. But it is the reduction in carrying a knife or another weapon (for protection or in case it is needed in a fight) that is most dramatic – declining from a prevalence level of around one in ten at age 12, and two in ten at age 14 amongst the ESYTC cohort, to less than 2% amongst the GUS cohort.

Figure one: Prevalence of self-reported offending at age 12 (ever) and age 14 (last year) amongst members of the ESYTC cohort (born 1986/87) and the GUS cohort (born 2004/05)

It is important to remember that the ESYTC and GUS studies have differences in design and methodology that might have impacted to some extent on the comparability of these data. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that these differences alone are responsible for the sheer extent of the sharp drop in offending between these two cohorts of young people. Moreover, there is evidence from other Scottish studies which support the claim that crime, and especially violence, has fallen most amongst younger members of society (see Matthews and Minton 2017; Skott and McVie 2019).

The much lower rate of involvement in violent offending – especially weapon carrying - amongst young people in contemporary Scottish society is to be celebrated, as it marks a welcome break from some of the cultures and traditions of previous generations. Nevertheless, it is important to avoid complacency and ensure that those young people who are still at higher risk of involvement in risky and problematic behaviours receive the support and encouragement they need to lead a life free from violence and disorder. Factors such as poverty and adverse child experiences remain strong predictors of engagement in childhood offending (Jahanshahi, Murray and McVie 2021), so policies such as the increased Scottish Child Payment and the ambition to build a trauma informed workforce across Scotland are essential.

For further information on the ESYTC and GUS studies:

https://www.edinstudy.law.ed.ac.uk/

https://growingupinscotland.org.uk/

References

Jahanshahi, B., Murray, K. and McVie, S. (2021) Aces, places and inequality: Understanding the effects of adverse childhood experiences and poverty on offending in childhood. British Journal of Criminology, 62(3): 751-772. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azab079

Matthews, B. and Minton, J. (2017) Rethinking one of Scotland’s brute facts: The age crime curve and the crime drop in Scotland. European Journal of Criminology, 15(3): 296-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817731706

Scottish Government (2022) Life at age 14: initial findings from the Growing Up in Scotland study. https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/research-and-analysis/2022/02/life-age-14-initial-findings-growing-up-scotland-study/documents/life-age-14-initial-findings-growing-up-scotland-study/life-age-14-initial-findings-growing-up-scotland-study/govscot%3Adocument/life-age-14-initial-findings-growing-up-scotland-study.pdf

McAra, L. and McVie, S. (2022) Causes and Impact of Offending and Criminal Justice Pathways: Follow-up of the Edinburgh Study Cohort at Age 35. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh. https://www.law.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-03/ESYTC%20Report%20%28March%202022%29%20-%20Acc.pdf

Skott, S. and McVie, S. (2019) Reductions in homicide and violence in Scotland is largely explained by fewer gangs and less knife crime. https://www.research.aqmen.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2020/02/S-Skott-Types-of-Homicide-28.1.19.pdf